The Kernel

Introduction

The kernel is the heart of the Linux operating system. It’s the software that takes the low-level requests, such as reading or writing files, or reading and writing general-purpose input/output (GPIO) pins, and maps them to the hardware. When you install a new version of the OS ([basics_latest_os]), you get a certain version of the kernel.

You usually won’t need to mess with the kernel, but sometimes you might want to try something new that requires a different kernel. This chapter shows how to switch kernels. The nice thing is you can have multiple kernels on your system at the same time and select from among them which to boot up.

|

Note

|

We assume here that you are logged on to your Bone as debian and have superuser privileges. You also need to be logged in to your Linux host computer as a nonsuperuser. |

Updating the Kernel

Problem

You have an out-of-date kernel and want to want to make it current.

Solution

Use the following command to determine which kernel you are running:

bone$ uname -a Linux beaglebone 3.8.13-bone67 #1 SMP Wed Sep 24 21:30:03 UTC 2014 armv7l GNU/Linux

The 3.8.13-bone67 string is the kernel version (which is really old).

To update to the current kernel, ensure that your Bone is on the Internet ([networking_usb] or [networking_wired]). Next follow [basics_find_image] and [basics_install_os] and [basics_update] to find the current image with the current kernel, install it and update it.

Building and Installing Kernel Modules

Problem

You need to use a peripheral for which there currently is no driver, or you need to improve the performance of an interface previously handled in user space.

Solution

The solution is to run in kernel space by building a kernel module. There are entire books on writing Linux Device Drivers. This recipe assumes that the driver has already been written and shows how to compile and install it. After you’ve followed the steps for this simple module, you will be able to apply them to any other module.

For our example module, download the cookbook repository and:

bone$ cd ~/BoneCookbook/docs/07kernel/code

And look at hello.c.

#include <linux/module.h> /* Needed by all modules */

#include <linux/kernel.h> /* Needed for KERN_INFO */

#include <linux/init.h> /* Needed for the macros */

static int __init hello_start(void)

{

printk(KERN_INFO "Loading hello module...\n");

printk(KERN_INFO "Hello, World!\n");

return 0;

}

static void __exit hello_end(void)

{

printk(KERN_INFO "Goodbye Boris\n");

}

module_init(hello_start);

module_exit(hello_end);

MODULE_AUTHOR("Boris Houndleroy");

MODULE_DESCRIPTION("Hello World Example");

MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");When compiling on the Bone, all you need to do is load the Kernel Headers for the version of the kernel you’re running:

bone$ sudo apt install linux-headers-`uname -r`

|

Note

|

The quotes around `uname -r` are backtick characters. On a United States keyboard, the backtick key is to the left of the 1 key. |

This took a little more than three minutes on my Bone. The `uname -r` part of the command looks up what version of the kernel you are running and loads the headers for it.

Next look at Makefile.

obj-m := hello.o

KDIR := /lib/modules/$(shell uname -r)/build

all:

<TAB>make -C $(KDIR) M=$$PWD

clean:

<TAB>rm hello.mod.c hello.o modules.order hello.mod.o Module.symvers|

Note

|

Replace the two instances of <TAB> with a tab character (the key left of the Q key on a United States keyboard). The tab characters are very important to makefiles and must appear as shown. |

Now, compile the kernel module by using the make command:

bone$ make make -C /lib/modules/5.10.120-ti-r48/build M=$PWD make[1]: Entering directory '/usr/src/linux-headers-5.10.120-ti-r48' CC [M] /home/debian/BoneCookbook/docs/07kernel/code/hello.o MODPOST /home/debian/BoneCookbook/docs/07kernel/code/Module.symvers CC [M] /home/debian/BoneCookbook/docs/07kernel/code/hello.mod.o LD [M] /home/debian/BoneCookbook/docs/07kernel/code/hello.ko make[1]: Leaving directory '/usr/src/linux-headers-5.10.120-ti-r48' bone$ ls Makefile hello.c hello.mod.c hello.o Module.symvers hello.ko hello.mod.o modules.order

Notice that several files have been created. hello.ko is the one you want. Try a couple of commands with it:

bone$ modinfo hello.ko filename: /home/debian/BoneCookbook/docs/07kernel/code/hello.ko license: GPL description: Hello World Example author: Boris Houndleroy depends: name: hello vermagic: 5.10.120-ti-r48 SMP preempt mod_unload modversions ARMv7 p2v8 bone$ sudo insmod hello.ko bone$ dmesg -H | tail -4 [ +0.000024] Bluetooth: BNEP filters: protocol multicast [ +0.000034] Bluetooth: BNEP socket layer initialized [Aug 8 13:49] Loading hello module... [ +0.000022] Hello, World!

The first command displays information about the module. The insmod command inserts the module into the running kernel. If all goes well, nothing is displayed, but the module does print something in the kernel log. The dmesg command displays the messages in the log, and the tail -4 command shows the last four messages. The last two messages are from the module. It worked!

Controlling LEDs by Using SYSFS Entries

Problem

You want to control the onboard LEDs from the command line.

Solution

On Linux, everything is a file; that is, you can access all the inputs and outputs, the LEDs, and so on by opening the right file and reading or writing to it. For example, try the following:

bone$ cd /sys/class/leds/ bone$ ls beaglebone:green:usr0 beaglebone:green:usr2 beaglebone:green:usr1 beaglebone:green:usr3

What you are seeing are four directories, one for each onboard LED. Now try this:

bone$ cd beaglebone\:green\:usr0

bone$ ls

brightness device max_brightness power subsystem trigger uevent

bone$ cat trigger

none nand-disk mmc0 mmc1 timer oneshot [heartbeat]

backlight gpio cpu0 default-on transient

The first command changes into the directory for LED usr0, which is the LED closest to the edge of the board. The [heartbeat] indicates that the default trigger (behavior) for the LED is to blink in the heartbeat pattern. Look at your LED. Is it blinking in a heartbeat pattern?

Then try the following:

bone$ echo none > trigger

bone$ cat trigger

[none] nand-disk mmc0 mmc1 timer oneshot heartbeat

backlight gpio cpu0 default-on transient

This instructs the LED to use none for a trigger. Look again. It should be no longer blinking.

Now, try turning it on and off:

bone$ echo 1 > brightness bone$ echo 0 > brightness

The LED should be turning on and off with the commands.

Controlling GPIOs by Using SYSFS Entries

Problem

You want to control a GPIO pin from the command line.

Solution

Controlling LEDs by Using SYSFS Entries introduces the sysfs. This recipe shows how to read and write a GPIO pin.

Reading a GPIO Pin via sysfs

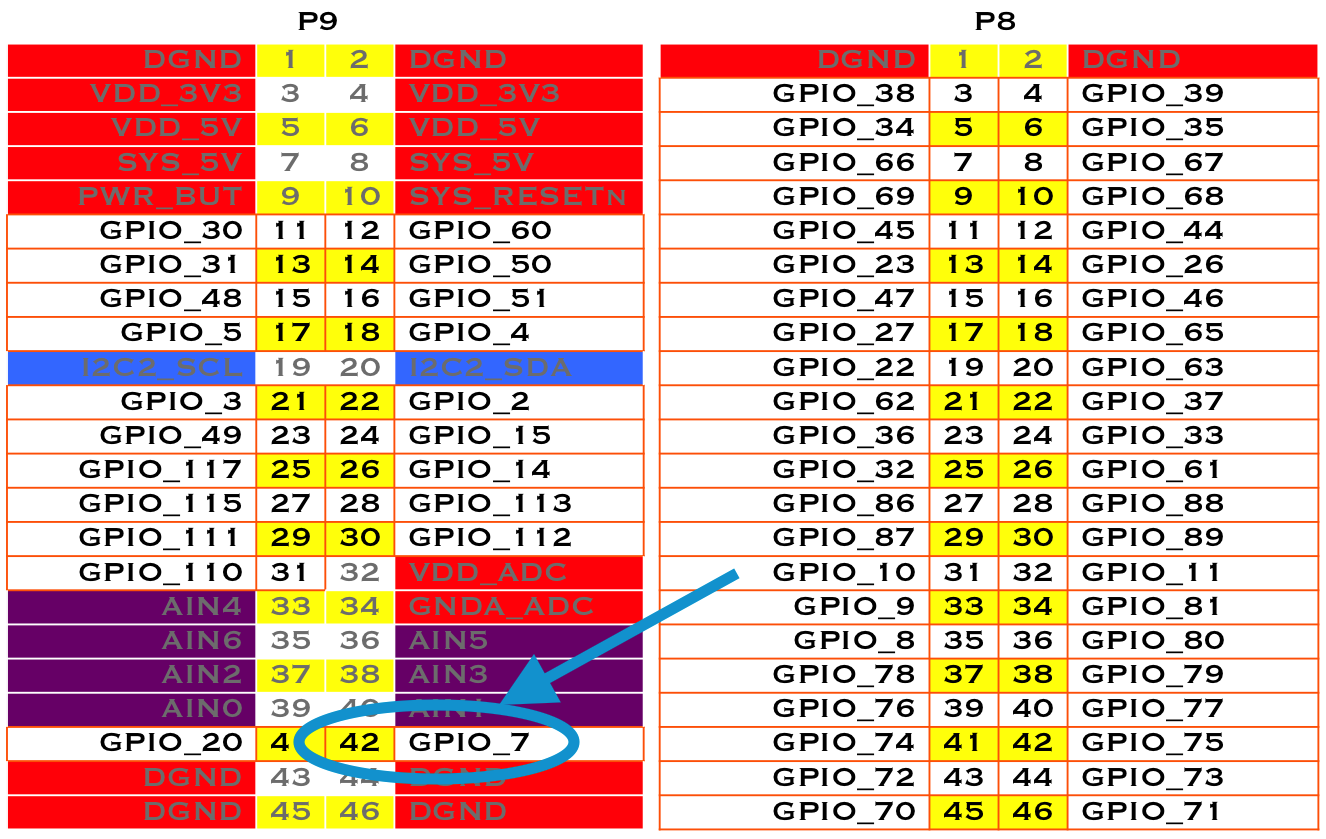

Suppose that you want to read the state of the P9_42 GPIO pin. ([sensors_pushbutton] shows how to wire a switch to P9_42.) First, you need to map the P9 header location to GPIO number using Mapping P9_42 header position to GPIO 7, which shows that P9_42 maps to GPIO 7. Or you can follow these [sensors_mappiing].

Next, change to the GPIO sysfs directory:

bone$ cd /sys/class/gpio/ bone$ ls export gpiochip0 gpiochip32 gpiochip64 gpiochip96 unexport

The ls command shows all the GPIO pins that have be exported. In this case, none have, so you see only the four GPIO controllers. Export using the export command:

bone$ echo 7 > export bone$ ls export gpio7 gpiochip0 gpiochip32 gpiochip64 gpiochip96 unexport

Now you can see the gpio7 directory. Change into the gpio7 directory and look around:

bone$ cd gpio7 bone$ ls active_low direction edge power subsystem uevent value bone$ cat direction in bone$ cat value 0

Notice that the pin is already configured to be an input pin. (If it wasn’t already configured that way, use echo in > direction to configure it.) You can also see that its current value is 0—that is, it isn’t pressed. Try pressing and holding it and running again:

bone$ cat value 1

The 1 informs you that the switch is pressed. When you are done with GPIO 7, you can always unexport it:

bone$ cd .. bone$ echo 7 > unexport bone$ ls export gpiochip0 gpiochip32 gpiochip64 gpiochip96 unexport

Writing a GPIO Pin via sysfs

Now, suppose that you want to control an external LED. [displays_externalLED] shows how to wire an LED to P9_14. Mapping P9_42 header position to GPIO 7 shows P9_14 is GPIO 50. Following the approach in Controlling GPIOs by Using SYSFS Entries, enable GPIO 50 and make it an output:

bone$ cd /sys/class/gpio/ bone$ echo 50 > export bone$ ls gpio50 gpiochip0 gpiochip32 gpiochip64 gpiochip96 bone$ cd gpio50 bone$ ls active_low direction edge power subsystem uevent value bone$ cat direction in

By default, P9_14 is set as an input. Switch it to an output and turn it on:

bone$ echo out > direction bone$ echo 1 > value bone$ echo 0 > value

The LED turns on when a 1 is written to value and turns off when a 0 is written.

Compiling the Kernel

Problem

You need to download, patch, and compile the kernel from its source code.

Solution

This is easier than it sounds, thanks to some very powerful scripts.

|

Warning

|

Be sure to run this recipe on your host computer. The Bone has enough computational power to compile a module or two, but compiling the entire kernel takes lots of time and resourses. |

Downloading and Compiling the Kernel

To download and compile the kernel, follow these steps:

host$ git clone git@github.com:RobertCNelson/ti-linux-kernel-dev.git # (1)

host$ cd ti-linux-kernel-dev/

host$ git tag # (2)

host$ git checkout 5.10.120-ti-r48 -b 5.10.120-ti-r48 # (3)

host$ time ./build_deb.sh # (4)-

The first command clones a repository with the tools to build the kernel for the Bone.

-

This command lists all the different versions of the kernel that you can build. You’ll need to pick one of these. How do you know which one to pick? A good first step is to choose the one you are currently running. uname -a will reveal which one that is. When you are able to reproduce the current kernel, go to Linux Kernel Newbies to see what features are available in other kernels. LinuxChanges shows the features in the newest kernel and LinuxVersions links to features of pervious kernels.

-

When you know which kernel to try, use git checkout to check it out. This command checks out at tag 3.8.13-bone60 and creates a new branch, v3.8.13-bone60.

-

build_kernel is the master builder. If needed, it will download the cross compilers needed to compile the kernel (linaro [http://www.linaro.org/] is the current cross compiler). If there is a kernel at ~/linux-dev, it will use it; otherwise, it will download a copy to ti-linux-kernel-dev/ignore/linux-src. It will then patch the kernel so that it will run on the Bone.

|

Note

|

Here is another repo to use for non-ti kernels. |

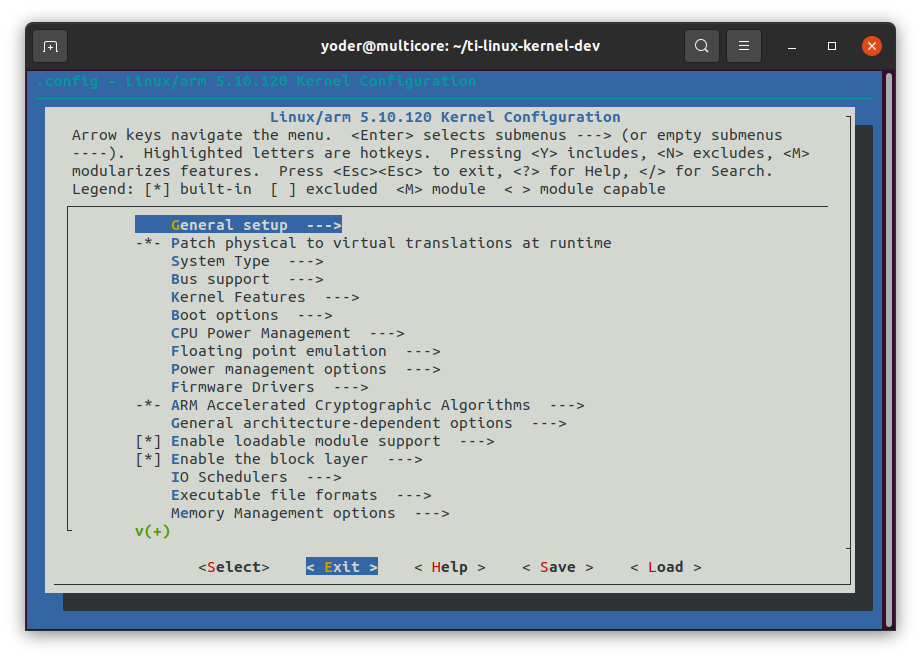

After the kernel is patched, you’ll see a screen similar to Kernel configuration menu, on which you can configure the kernel.

You can use the arrow keys to navigate. No changes need to be made, so you can just press the right arrow and Enter to start the kernel compiling. The entire process took about 25 minutes on my 8-core host.

The ti-linux-kernel-dev/KERNEL directory contains the source code for the kernel. The ti-linux-kernel-dev/deploy directory contains the compiled kernel and the files needed to run it.

Installing the Kernel on the Bone

The ./build_deb.sh script creates a single .deb file that contains all the files needed for the new kernel. You find it here:

host$ cd ti-linux-kernel-dev/deploy host$ ls -sh total 42M 7.7M linux-headers-5.10.120-ti-r48_1xross_armhf.deb 8.0K linux-upstream_1xross_armhf.buildinfo 33M linux-image-5.10.120-ti-r48_1xross_armhf.deb 4.0K linux-upstream_1xross_armhf.changes 1.1M linux-libc-dev_1xross_armhf.deb

The linux-image- file is the one we want. It contains over 3000 files.

host$ dpkg -c linux-image-5.8.11-bone17_1xross_armhf.deb | wc 3177 19062 371016

The dpkg -c command lists the contents (all the files) in the .deb file and the wc counts all the lines in the output. You can see those files with:

bone$ dpkg -c linux-image-5.8.11-bone17_1xross_armhf.deb | less drwxr-xr-x root/root 0 2022-08-08 22:43 ./ drwxr-xr-x root/root 0 2022-08-08 22:43 ./boot/ -rw-r--r-- root/root 4749032 2022-08-08 22:43 ./boot/System.map-5.10.120-ti-r48 -rw-r--r-- root/root 190604 2022-08-08 22:43 ./boot/config-5.10.120-ti-r48 drwxr-xr-x root/root 0 2022-08-08 22:43 ./boot/dtbs/ drwxr-xr-x root/root 0 2022-08-08 22:43 ./boot/dtbs/5.10.120-ti-r48/ -rwxr-xr-x root/root 90652 2022-08-08 22:43 ./boot/dtbs/5.10.120-ti-r48/am335x-baltos-ir2110.dtb -rwxr-xr-x root/root 91370 2022-08-08 22:43 ./boot/dtbs/5.10.120-ti-r48/am335x-baltos-ir3220.dtb -rwxr-xr-x root/root 91641 2022-08-08 22:43 ./boot/dtbs/5.10.120-ti-r48/am335x-baltos-ir5221.dtb -rwxr-xr-x root/root 88692 2022-08-08 22:43 ./boot/dtbs/5.10.120-ti-r48/am335x-base0033.dtb -rwxr-xr-x root/root 197471 2022-08-08 22:43 ./boot/dtbs/5.10.120-ti-r48/am335x-bone-uboot-univ.dtb

You can see it’s putting things in the /boot directory.

|

Note

|

You can also look into the other two .deb files and see what they install. |

Move the linux-image- file to your Bone.

host$ scp linux-image-5.10.120-ti-r48_1xross_armhf.deb bone:.

Hint: You might have to use debian@192.168.7.2 for bone if you haven’t set everything up.

Now ssh to the bone.

host$ ssh bone bone$ ls -sh bin exercises linux-image-5.10.120-ti-r48_1xross_armhf.deb

Now install it.

bone$ sudo dpkg --install linux-image-5.10.120-ti-r48_1xross_armhf.deb

Wait a while. Once done check /boot.

bone$ ls -sh /boot total 122M 188K config-5.10.120-ti-r46 7.6M initrd.img-5.10.120-ti-rt-r47 4.0K uEnv.txt 188K config-5.10.120-ti-r47 13M initrd.img-5.10.120-ti-rt-r48 4.0K uEnv.txt.orig 188K config-5.10.120-ti-r48 4.0K SOC.sh 9.9M vmlinuz-5.10.120-ti-r46 188K config-5.10.120-ti-rt-r47 4.5M System.map-5.10.120-ti-r46 11M vmlinuz-5.10.120-ti-r47 188K config-5.10.120-ti-rt-r48 4.6M System.map-5.10.120-ti-r47 11M vmlinuz-5.10.120-ti-r48 4.0K dtbs 4.6M System.map-5.10.120-ti-r48 11M vmlinuz-5.10.120-ti-rt-r47 7.5M initrd.img-5.10.120-ti-r46 4.6M System.map-5.10.120-ti-rt-r47 11M vmlinuz-5.10.120-ti-rt-r48 7.6M initrd.img-5.10.120-ti-r47 4.6M System.map-5.10.120-ti-rt-r48 13M initrd.img-5.10.120-ti-r48 4.0K uboot

You see the new kernel files. Check uEnv.txt.

bone$ head /boot/uEnv.txt #Docs: http://elinux.org/Beagleboard:U-boot_partitioning_layout_2.0 uname_r=5.10.120-ti-r48 # uname_r=5.10.120-ti-rt-r47

I added the commented out uname_r line to make it easy to switch between versions of the kernel.

Reboot and test out the new kernel.

bone$ sudo reboot bone$ uname -a Linux breadboard-home 5.10.120-ti-r48 #1xross SMP PREEMPT Mon Aug 8 18:30:51 EDT 2022 armv7l GNU/Linux

Using the Installed Cross Compiler

Problem

You have followed the instructions in Compiling the Kernel and want to use the cross compiler it has downloaded.

|

Tip

|

You can cross-compile without installing the entire kernel source by running the following: host$ sudo apt install gcc-arm-linux-gnueabihf Then skip down to Setting Up Variables. |

Solution

Compiling the Kernel installs a cross compiler, but you need to set up a couple of things so that it can be found. Compiling the Kernel installed the kernel and other tools in a directory called ti-linux-kernel-dev. Run the following commands to find the path to the cross compiler:

host$ cd ti-linux-kernel-dev/dl host$ ls gcc-10.3.0-nolibc x86_64-gcc-10.3.0-nolibc-arm-linux-gnueabi.tar.xz

Here, the path to the cross compiler contains the version number of the compiler. Yours might be different from mine. cd into it:

host$ cd gcc-10.3.0-nolibc/arm-linux-gnueabi host$ ls 2020.10.3.0-arm-linux-gnueabi arm-linux-gnueabi bin include lib libexec share x

At this point, we are interested in what’s in bin:

host$ cd bin host$ ls arm-linux-gnueabi-addr2line arm-linux-gnueabi-gcc-nm arm-linux-gnueabi-nm arm-linux-gnueabi-ar arm-linux-gnueabi-gcc-ranlib arm-linux-gnueabi-objcopy arm-linux-gnueabi-as arm-linux-gnueabi-gcov arm-linux-gnueabi-objdump arm-linux-gnueabi-c++filt arm-linux-gnueabi-gcov-dump arm-linux-gnueabi-ranlib arm-linux-gnueabi-cpp arm-linux-gnueabi-gcov-tool arm-linux-gnueabi-readelf arm-linux-gnueabi-elfedit arm-linux-gnueabi-gprof arm-linux-gnueabi-size arm-linux-gnueabi-gcc arm-linux-gnueabi-ld arm-linux-gnueabi-strings arm-linux-gnueabi-gcc-10.3.0 arm-linux-gnueabi-ld.bfd arm-linux-gnueabi-strip arm-linux-gnueabi-gcc-ar arm-linux-gnueabi-lto-dump

What you see are all the cross-development tools. You need to add this directory to the $PATH the shell uses to find the commands it runs:

host$ pwd /home/yoder/ti-linux-kernel-dev/dl/gcc-10.3.0-nolibc/arm-linux-gnueabi/bin host$ echo $PATH /usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin:/usr/games:/usr/local/games:/snap/bin

The first command displays the path to the directory where the cross-development tools are located. The second shows which directories are searched to find commands to be run. Currently, the cross-development tools are not in the $PATH. Let’s add it:

host$ export PATH=`pwd`:$PATH host$ echo $PATH /home/yoder/ti-linux-kernel-dev/dl/gcc-10.3.0-nolibc/arm-linux-gnueabi/bin:/usr/local/sbin:/usr/local/bin:/usr/sbin:/usr/bin:/sbin:/bin:/usr/games:/usr/local/games:/snap/bin

|

Note

|

Those are backtick characters (left of the "1" key on your keyboard) around pwd. |

The second line shows the $PATH now contains the directory with the cross-development tools.

Setting Up Variables

Now, set up a couple of variables to know which compiler you are using:

host$ export ARCH=arm host$ export CROSS_COMPILE=arm-linux-gnueabi-

These lines set up the standard environmental variables so that you can determine which cross-development tools to use. Test the cross compiler by adding Simple helloWorld.c to test cross compiling (helloWorld.c) to a file named helloWorld.c.

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

printf("Hello, World! \n");

}You can then cross-compile by using the following commands:

host$ ${CROSS_COMPILE}gcc helloWorld.c

host$ file a.out

a.out: ELF 32-bit LSB executable, ARM, version 1 (SYSV),

dynamically linked (uses shared libs), for GNU/Linux 2.6.31,

BuildID[sha1]=0x10182364352b9f3cb15d1aa61395aeede11a52ad, not stripped

The file command shows that a.out was compiled for an ARM processor.

Applying Patches

Problem

You have a patch file that you need to apply to the kernel.

Solution

Simple kernel patch file (hello.patch) shows a patch file that you can use on the kernel.

From eaf4f7ea7d540bc8bb57283a8f68321ddb4401f4 Mon Sep 17 00:00:00 2001

From: Jason Kridner <jdk@ti.com>

Date: Tue, 12 Feb 2013 02:18:03 +0000

Subject: [PATCH] hello: example kernel modules

---

hello/Makefile | 7 +++++++

hello/hello.c | 18 ++++++++++++++++++

2 files changed, 25 insertions(+), 0 deletions(-)

create mode 100644 hello/Makefile

create mode 100644 hello/hello.c

diff --git a/hello/Makefile b/hello/Makefile

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..4b23da7

--- /dev/null

+++ b/hello/Makefile

@@ -0,0 +1,7 @@

+obj-m := hello.o

+

+PWD := $(shell pwd)

+KDIR := ${PWD}/..

+

+default:

+ make -C $(KDIR) SUBDIRS=$(PWD) modules

diff --git a/hello/hello.c b/hello/hello.c

new file mode 100644

index 0000000..157d490

--- /dev/null

+++ b/hello/hello.c

@@ -0,0 +1,22 @@

+#include <linux/module.h> /* Needed by all modules */

+#include <linux/kernel.h> /* Needed for KERN_INFO */

+#include <linux/init.h> /* Needed for the macros */

+

+static int __init hello_start(void)

+{

+ printk(KERN_INFO "Loading hello module...\n");

+ printk(KERN_INFO "Hello, World!\n");

+ return 0;

+}

+

+static void __exit hello_end(void)

+{

+ printk(KERN_INFO "Goodbye Boris\n");

+}

+

+module_init(hello_start);

+module_exit(hello_end);

+

+MODULE_AUTHOR("Boris Houndleroy");

+MODULE_DESCRIPTION("Hello World Example");

+MODULE_LICENSE("GPL");Here’s how to use it:

-

Install the kernel sources (Compiling the Kernel).

-

Change to the kernel directory (cd ti-linux-kernel-dev/KERNEL).

-

Add Simple kernel patch file (hello.patch) to a file named hello.patch in the ti-linux-kernel-dev/KERNEL directory.

-

Run the following commands:

host$ cd ti-linux-kernel-dev/KERNEL host$ patch -p1 < hello.patch patching file hello/Makefile patching file hello/hello.c

The output of the patch command apprises you of what it’s doing. Look in the hello directory to see what was created:

host$ cd hello host$ ls hello.c Makefile

Discussion

Building and Installing Kernel Modules shows how to build and install a module, and Creating Your Own Patch File shows how to create your own patch file.

Creating Your Own Patch File

Problem

You made a few changes to the kernel, and you want to share them with your friends.

Solution

Create a patch file that contains just the changes you have made. Before making your changes, check out a new branch:

host$ cd ti-linux-kernel-dev/KERNEL host$ git status # On branch master nothing to commit (working directory clean)

Good, so far no changes have been made. Now, create a new branch:

host$ git checkout -b hello1 host$ git status # On branch hello1 nothing to commit (working directory clean)

You’ve created a new branch called hello1 and checked it out. Now, make whatever changes to the kernel you want. I did some work with a simple character driver that we can use as an example:

host$ cd ti-linux-kernel-dev/KERNEL/drivers/char/ host$ git status # On branch hello1 # Changes not staged for commit: # (use "git add file..." to update what will be committed) # (use "git checkout -- file..." to discard changes in working directory) # # modified: Kconfig # modified: Makefile # # Untracked files: # (use "git add file..." to include in what will be committed) # # examples/ no changes added to commit (use "git add" and/or "git commit -a")

Add the files that were created and commit them:

host$ git add Kconfig Makefile examples host$ git status # On branch hello1 # Changes to be committed: # (use "git reset HEAD file..." to unstage) # # modified: Kconfig # modified: Makefile # new file: examples/Makefile # new file: examples/hello1.c # host$ git commit -m "Files for hello1 kernel module" [hello1 99346d5] Files for hello1 kernel module 4 files changed, 33 insertions(+) create mode 100644 drivers/char/examples/Makefile create mode 100644 drivers/char/examples/hello1.c

Finally, create the patch file:

host$ git format-patch master --stdout > hello1.patch